Click here to see the slides for the presentation at CEPDISC’22 Conference on Discrimination, ACES 2022 at Utrecht University, International Conference on Social Dilemmas at Uni Copenhagen, In_Equality Colloquim at Uni Konstanz, 14th Annual INAS conference, the Colloquium for Analytical Sciology at EUI.

Abstract: How accurate do persons of immigrant origin perceive the extent of ethnic discrimination they face? Theoretical and empirical scholarship on this question is rare and arguably underdeveloped. The challenge lies in comparing individuals’ perceptions and expectations of discrimination against the actual discrimination they face personally. So far, we lack a methodology to gather such data and with it the foundation to develop a sociology of misperceived discrimination.

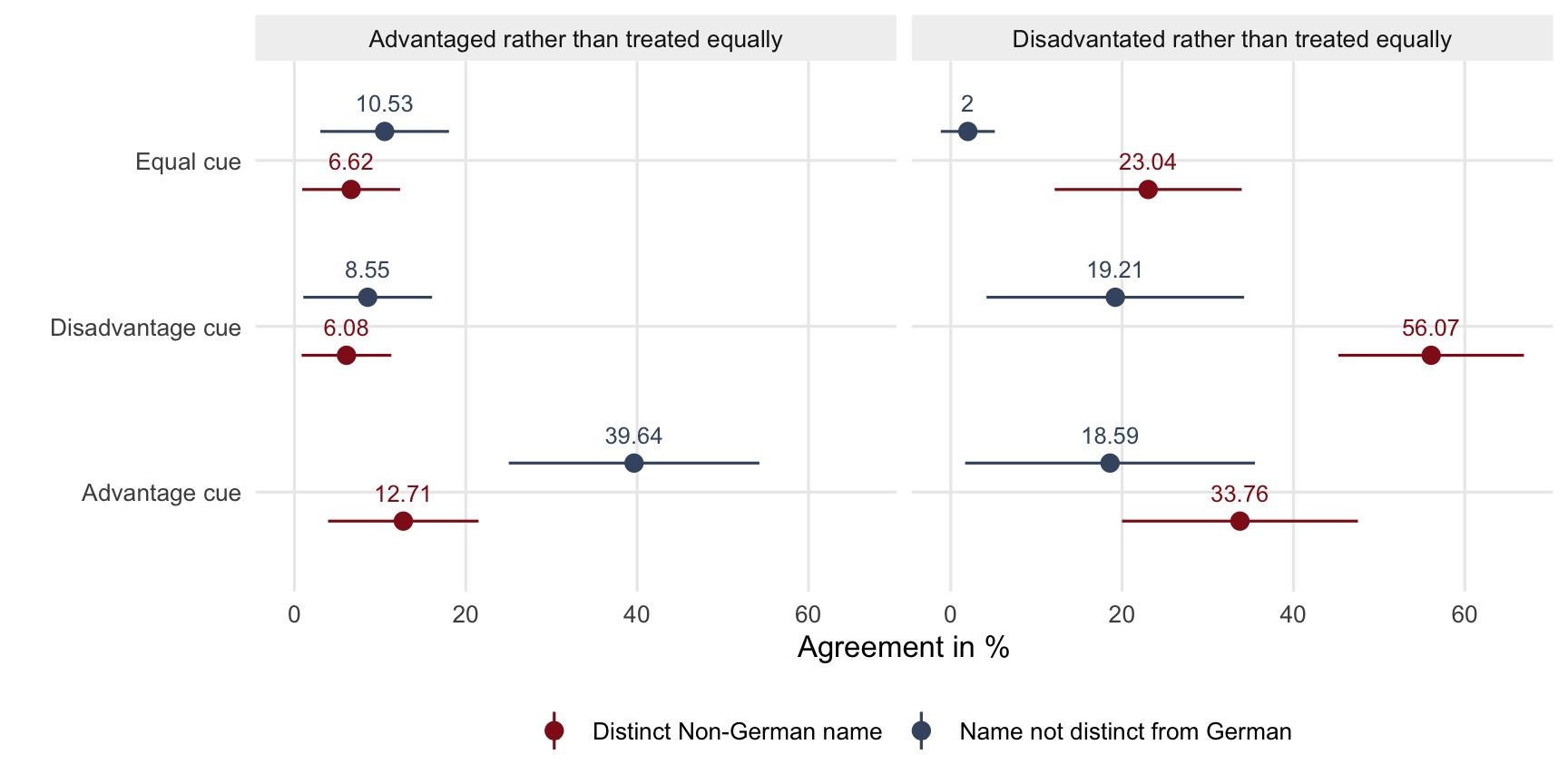

The current study proposes a methodology to measure misperceptions of mistrust-based ethnic discrimination. The starting point of the methodology we propose is that behavioral games, such as the trust game, are based on the mutual evaluation of study participants. Prior research has therefore extensively used behavioral games to measure name-based ethnic discrimination. We extent this line of research by exploiting the hitherto overlooked possibility to also survey perceived discrimination in terms of whether participants expect to be discriminated by their game partners. Importantly, this allows us to measure expected and actual discrimination on the same scale and to thus go beyond estimating an association and in fact present a first measure of individual’s over- and under-perceptions of ethnic discrimination. To measure perceived rather than expected discrimination more directly, we further conduct a follow-up experiment that mimics the every-day life situation in which minorities need to decide whether they frame an anecdotal event of disadvantage as an experience of intentional discrimination. To do so, we inform participants about their average payoffs from the trust games and randomly treat them with a favorable, unfavorable, or equal comparison to the payoffs of native-named participants. We then study whether participants correctly perceive these comparisons as reflecting intentional discrimination or rather as an instance of bad luck. Finally, this also allows us to investigate to which extent persons correctly generalize from their personal anecdotal event of disadvantage to their group at large: we ask participants whether they think that persons with the same first name as their own where generally discriminated in the trust games. We pre-registered and then implemented this new methodology among a register-based random sample of 1,000 persons of immigrant origin and 1,000 mainstream Germans with German-born parents. We finalized data collection on 27 March ’22 and present preliminary results.

Were participants called “YOUR NAME” generally advantaged, treated equally, or disadvantaged by their game partners?

Note: These are very preliminary findings!

Note: These are very preliminary findings!